The noise surrounding which system is better has gone on long enough and has not led to any useful conclusions. So rather than add to the noise, I would like to touch on the relevance this may have for the Craft, and suggest a pragmatic approach. My view (based on what I’ve learnt as Paul’s apprentice) is that anyone who has understood and become competent at working with both metric and imperial will inevitably find themselves using imperial primarily in their woodworking.

If we are to analyse the issue from the point of view of the Craft, a good place to begin would be to ask what the Craft is concerned with, as well as what it’s not. Only then will we be in a place to ask what the benefits of each unit may be.

The Craft

The Craft is about creating functional pieces out of wood, somewhat efficiently yet not so much that you deprive yourself of the challenge that skilled work demands –i.e. by becoming an operator who ‘outsources’ the real work to machines. Now it’s vital to say at this point that learning efficiency takes time, so nobody should feel guilty if they feel that they’re taking forever to complete a project. Personally, it took me a number of years to realise that it wasn’t enough to be able to complete a project, but I had to do it in a reasonable amount of time. Until that happened, my woodworking was really just a hobby, a pastime, which is fine, but it’s unsustainable for anyone who aspires to be a crafting man or woman.

As for what the Craft is NOT, it’s definitely not about creating perfectly uniform pieces with no discrepancies whatsoever (here is where the concept of ‘flatness’ can easily become an obsession). It is of no interest to the Craft that things are made in such a way that they could pass as machine-made, nor is the Craft concerned with replicating other’s projects (or even your own) exactly, i.e. to the millimetre. This is simply obsessive, and even though it’s everyone’s right to spend their time and resources as they please, we cannot in any way accept that this is part of the Craft. Again, I must point out that I myself fell into this trap numerous times, and only in recent years did I begin to develop a crafting mindset, mainly by recognising which popular practices, habits and values have nothing to do with the Craft. Or, as Paul would say, “Sometimes we have to see what something is not to see what it really is“1.

If we agree, then, that efficiency is central to the Craft, then a key concept is economy of motion. Paul has so often talked/written about this, which is essential to developing a crafting mindset. Economy of motion involves learning to work systematically, for example doing all your layout at once, as well as using the most efficient techniques for each task, like splitting off, rather than sawing your tenon cheeks. Note that, very often, the most efficient techniques require more skill, therefore we can say that skill makes you a better artisan in that you’re more efficient, or more productive, and not that the end result is necessarily better. Another example of economy of motion would be developing ambidexterity so that you can work from both directions; this saves you having to keep turning a workpiece in the vise. These are only a few of countless such practices applicable in a crafting artisan’s everyday life, all of which point to saving resources.

Whilst economy of motion is about saving physcial resources (energy, but also time), we can also talk about saving mental resources (we could call this economy of neurological motion). This has to do with lightening the load in your head by minimising the information that you need to remember so that you can get on with the task at hand. When it comes to units of measure, common sense tells us that we choose the most convenient unit for each scenario. For example, a few years ago, when inquiring about siding boards in my hometown, the shop manager told me the length of the boards in metres (1.8m), the width in centimetres (20cm) and the thickness in millimetres (13mm). The information was clear, easy to assimilate and work with for any necessary calculations.

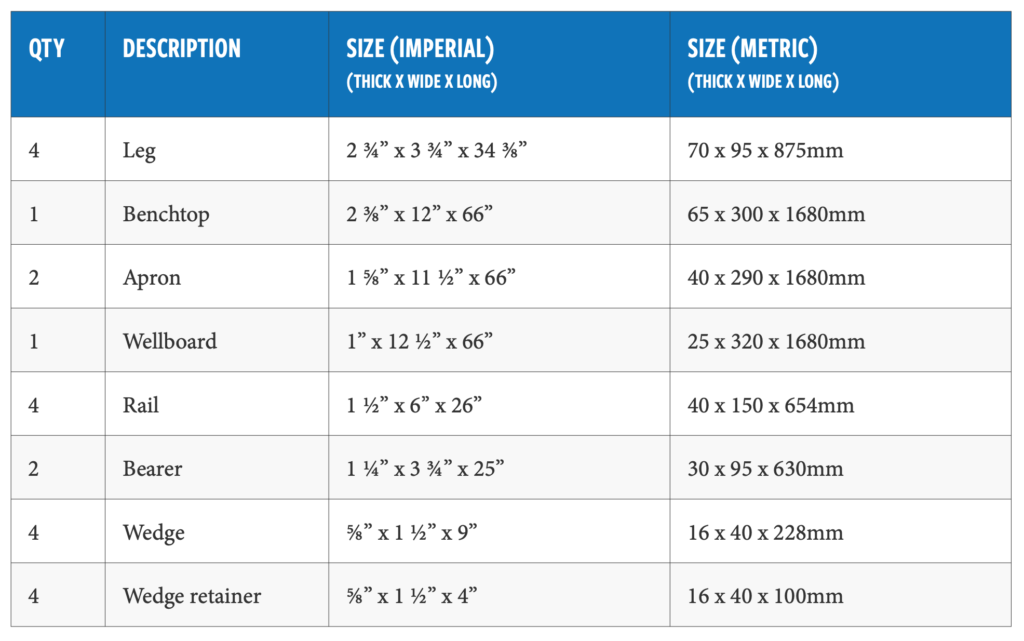

With inches (and fractions of inches) it’s the same. Whole inches are good enough for most general approximations (including a person’s height, I recently found), whilst half-inches, quarter-inches, eighths, sixteenths and so on (though rarely necessary) provide increasing precision as the situation demands it. The cutting list below (for the Paul Sellers Workbench) clearly illustrates this point.

If the whole debate were simply about which system used whole numbers, the millimetre would win every time. That’s why hobbyists love them; that is, pastime woodworkers, who represent a percentage of Paul’s following and of the woodworking population in general. And that’s also why Paul kindly includes metric measurements for his projects. However, with millimetres you end up working with ridiculously large numbers: one thousand, six hundred and eighty millimetres for the length of a benchtop.

Given that the inch is 25 times larger than the millimetre, any value expressed in cm will be 25 times the same measurement in inches (i.e. 66″ as opposed to 1680mm). Though there’s already a benefit in working with smaller numbers, the main difference between metric and imperial is clearly seen when whole inches or whole centimetres are too big, and you need more precision.

With inches, as discussed above, you can use increasing levels of precision as the situation demands. With metric, half-centimetres might sometimes be sufficient, and thankfully most tape measures and steel rules have such markings. However, more often than not you will need something in between, so you have to go with millimetres, which are ten times smaller than the centimetre, and are generally an overkill. If you don’t agree, ask yourself, how often does Paul use sixteenths of an inch on a project (which are even bigger than 1mm)? My point is this: millimetric precision is hardly ever needed in hand-tool woodworking. Most often, 1/8″ (equivalent to about 3mm) is precise enough, though occasionally, on smaller projects you might need 1/16″.

Reference, not exact measurement

At this point we should note that measurements themselves are often just something to work towards; even though we always try to work accurately, not all measurements are equally critical: the length of four table legs should be pretty much the same, but there is a lot more tolerance on the overhang on the sides of a tabletop, as this is purely aesthetic. Furthermore, many times a measurement may be unnecessary altogether. For instance, when thicknessing 1″ stock (which always varies if rough-sawn), I often set a gauge, or the fence on the bandsaw, to obtain the thickest board I can get, whatever that might be, and once thicknessed, I won’t even measure it; I know it will work because it’s within the acceptable margin for what I am working on.

Note that I’m not speaking just from my very limited experience, nor from what I’ve learned from Paul over the years. Looking at furniture pieces made by craftsmen of old (the men who handed down the Craft to us), you will often find that their components differ in thickness as they weren’t in the least bit concerned with replicating what machines do. They were concerned about making functional pieces that were aesthetically pleasing, wasting as little time as possible. The bottom line is: there is always an acceptable tolerance within which you can work and still end up with a good product. Mastering the Craft has a lot to do with finding these tolerances.

Conclusion

Despite my belief that inches is the unit par excellence of the Craft, I do believe that there is a place for metric, and that anyone aspiring to embrace the Craft would benefit from getting acquainted with both systems. Don’t just take my word for it, see for yourself. Get hold of a tape measure, rule and square with both imperial and metric markings, take the trouble to recap basic fractions, and soon you will be able to judge for yourself which of the two most facilitates your journey to becoming a true artisan, who not only creates like a crafting man or woman but also thinks like one.

Millimetres a good for metal working and engineering (always using 10³ like units to avoid errors), but for woodworking I would prefer cm.

By the way, it is what I first used at primary school about 65 years ago (nice on a school notebook for a young kid with yet undevelopped dexterity).

One will notice that furniture dimensions are given in cm on the web site of big companies (like §K&@).

Although, for the kind of woodworking I do, I generally work by reference and not by given dimensions.

I recently made the following comment on woodworking masterclasses following another comment about errors in conversions given by Paul Sellers’ team:

“I don’t think converting inches to mm is a good idea.

It usually gives weird numbers.

I would like dimensions which are rounded in cm (with a 0.5 cm precision if useful).

Changing all the dimensions to give nice numbers for metric people (like me) would, of course, be a lot of extra work for Joseph 😉 .

So, unless I change all the dimensions myself, while keeping the whole thing coherent for assembly, I will use the foot and inches [as given].

Changing to round cm might also need slightly different angles where things are not square…”

A good example of silly numbers are the rail and wedge dimensions in the conversion table you reproduced. Making it round numbers in cm will not compromise the workbench (mine has other dimensions as I adapted to the recycled material available).